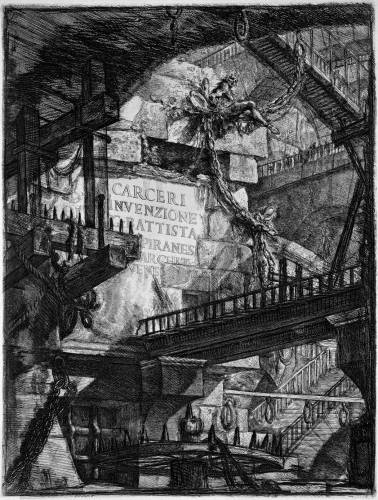

He has drawn with dust, chocolate, sugar, fake blood and skywriting smoke. The Brazilian-born, New York-based Muniz is known for photographs of images he makes with quirky, often fugitive substances. Other workers still were required to build them and staff them. Underlying the brooding, dizzying grandeur is an Enlightenment-era understanding that for "Abandon All Hope" to be emblazoned above the gates of Hell, somebody had to inscribe it there. Their vastness connotes not so much a sublime terror as the notion of Hell as an enormous bureaucracy. Regardless of the diagnosis, evidence of a proto-romantic sensibility can be found in the sheer outlandishness of the scale of Piranesi's spaces. It was amid the ancient ruins of Rome, however, that his imagination found a platform on which to play out its schemes.Īs legend has it, the Carceri are the stuff of fever dreams, conceived during a bout of malaria. Born a Venetian, with all the love of theatricality that implies, he was a student of stage design as well as architecture. Piranesi (1720-78) was in his twenties when he made the first edition of plates for what he would later call his Carceri d'Invenzione.

It's on view at the National Academy of Sciences. Successive generations just naturally find their way through the twisting staircases and cavernous vaults to walk among the ropes and chains and thrill to the smoking braziers, spiked wheels and other instruments of torture.īut an installation that pairs the portfolio of 18th-century etchings with new photos of string-art re-creations of them by contemporary artist Vik Muniz offers a timely reinterpretation of Piranesi's architectural allegories of power. The dark, dreamlike images are broadly circulated, widely reproduced and possessed of great visual appeal and narrative implication. In this article, these questions are asked in relation to the history of prison architecture, from premodern times to the present, while considering the multiple discourses that overlap throughout that history: war, enslavement, civil punishment, and freedom struggle, but also a discourse of agency, where subordinated peoples can or cannot resist, or remain hostile to or in difference from the control placed upon them.Giovanni Battista Piranesi's Prisons of the Imagination aren't exactly begging to have new life breathed into them.

They also shape the politics of freedom and control, where what might be a free, privileged expression to one person could be a dangerous exposure to another, where invisibility or inscrutability may be a resource. Images, architecture, light, presentation and camouflage, surveillance, and the play of sight between groups of people and the world are all materials through which the ideas of a society are worked out, its politics played out, its technology implemented, its rationality or common sense and identities forming. In terms of its visual culture, that relationship forms a visuality, a culture and politics of vision that both reflects the state’s carceral qualities and, in turn, helps to structure and organize the society in a carceral manner. In addition to the budgets, routines, and technologies used is the culture of that carceral state, where relationships form between elements of its culture and its politics.

As we begin to think about the United States as a carceral state, this means that the scale of incarceration practices have grown so great within it that they have a determining effect on the shape of the the society as a whole.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)